Image credit: Flickr/katinka01

This piece was published in Croakey on 10 February 2020. It was edited for Croakey by Amy Coopes.

One of the reasons Prime Minister Scott Morrison has given for not bolstering emissions reduction targets is his belief that building resilience for the future is a better way to go.

Speaking to reporters at Parliament House on January 14, this is what he had to say:

I’ve set out what I think we need to do in terms of the future and that has been very much ensuring that we continue to meet and beat the emissions reduction targets that we’ve set. I’ve said, though, I think more significantly that resilience and adaptation need an even greater focus.

The practical thing that actually can most keep you safe during the next fire or the next flood or the next cyclone are the things that most benefit people here and now… The emissions reduction activity of any one country anywhere in the world is not going to specifically stop or start one fire event but what the climate resilience and adaptation work can do within a country can very much directly ensure that Australians are better protected against what this reality is in the future.

We must build our resilience for the future, and that must be done on the science and the practical realities of the things we can do right here to make a difference.”

His address to the National Press Club on January 29 featured 16 references to ‘resilience’. They included an assertion about the economy’s resilience, resilience to natural disasters, to a changing climate, and to unspecified other threats. He spoke of national resilience, practical action on climate resilience and adaptation, and asserted that mitigation and adaptation both contribute to resilience.

Farmers, he said, are on the frontline of resilience.

“The $5 billion Future Drought Fund will support practical, resilience-building measures, including small-scale water infrastructure and improved information on local climate variability, sustainable stock management, soil and water regeneration and the like. Our Drought Resilience Funding Plan — the framework to guide funding decisions for projects and activities — is expected to be tabled in Parliament by March of this year,” he said.

The Reef 2050 Plan and investments in “the technology of resilience, science of resilience through agencies such as the Bureau of Meteorology, the CSIRO and the Bushfire & Natural Hazards CRC” were among other measures touted by the Prime Minister in his address.

Looking ahead, he said he had tasked the CSIRO with bringing forward recommendations, supported by an expert advisory panel chaired by Australia’s chief scientist, on “further practical resilience measures, including buildings, public infrastructure, industries such as agriculture, and protecting our natural assets.”

Added Morrison:

I will be discussing resilience measures with the states and territories at COAG in March, and I know they’re looking forward to that discussion, including to ensure the Commonwealth Government’s investment through the National Bushfire Recovery Agency will be in assets that are built to last, built to resist, built to survive longer, hotter, drier summers. Building Back Better for the future.”

But what exactly is this ‘resilience’ of which much is expected? Do we all share a common view of what it is, what it does, and how more of it can be created?

Resilience defined

resilience /rɪˈzɪlɪəns/

noun: resilience; noun: resiliency; plural noun: resiliencies

- the power or ability to return to the original form, position, etc., after being bent, compressed, or stretched; elasticity.

- ability to recover readily from illness, depression, adversity, or the like; buoyancy.

The first thing to note is that ‘resilience’ is a positive thing – an asset. In this particular definition, resilience is a power or an ability.

When applied to a physical entity, resilience refers to its capacity to return to original shape, following the application of external pressure. In such a case, resilience is attributable to the properties of the substances of which the entity is made.

The extension of this notion to human communities is easy and pleasing. The individuals in the community are the constituent parts, akin to the molecules that provide a substance with its physical properties. The property of a particular community with respect to resilience is determined by the individuals in it, the relationship between them and their aggregated response to an external force.

There is a large and rich literature on community and personal resilience, traversing disciplines such as psychology, sociology, engineering, geography and management.

One systematic literature review of definitions of community resilience related to disasters published in 2017 found no evidence of a common, agreed definition. It did, however, identify nine common core elements of community resilience. They are:

- local knowledge

- community networks and relationships

- communication

- health

- governance and leadership

- resources

- economic investment

- preparedness

- mental outlook

The study notes that due to climate change and demographic movements into large cities, disasters are occurring more frequently and in many cases with higher intensity than in previous years. This has prompted a stronger focus on how best to help communities to help themselves, with a concomitant focus on understanding what factors contribute to making a community resilient to disasters.

The authors write:

The concept of ‘community resilience’ is almost invariably viewed as positive, being associated with increasing local capacity, social support and resources, and decreasing risks, miscommunication and trauma.

Yet consensus as to what community resilience is, how it should be defined, and what its core characteristics are does not appear to have been reached, with mixed definitions appearing in the scientific literature, policies and practice. This confusion is troubling.

The way we define community resilience affects how we attempt to measure and enhance it.”

So community resilience is something that cannot be identified at a single point in time, but over time — in particular over the period after a community has been exposed to pressure.

How did the community respond? Did it return to its original shape, form and pattern of behaviour?

Resilience located

People who live in communities that can rebound are the lucky ones.The lives of many others are characterised by pressure and deprivation, but without the resources (the skills, financial means, information, personal health etc) and equitable access to the supports required to bounce back.

There are a number of educational resources relating to the fostering of resilience. One has it that the seven Cs of resilience are competence, confidence, connection, character, contribution, coping, and control. Another asserts that resilience is made up of five pillars: self awareness, mindfulness, self care, positive relationships and purpose.

I am familiar with the term and its application from my time working for the National Rural Health Alliance as a rural advocate. One of the purposes of that work was to try to ensure that rural issues were ‘on the agenda’.

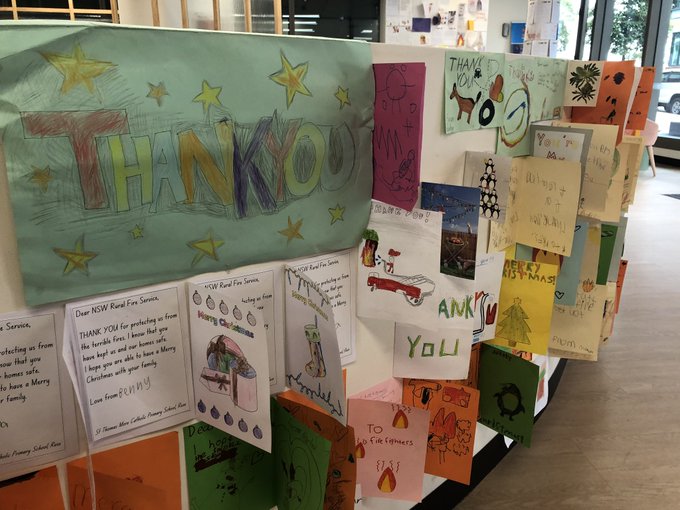

This season’s bushfires have thrown the public spotlight on rural and remote areas like almost never before, also highlighting the community spirit which commonly exists in them. We have been reminded daily of the devotion of individuals who serve rural communities so expertly and selflessly: in rural fire services, the SES, Shire Councils, charitable organisations, the State and Federal public service, and many other bodies.

Though not exclusively a rural phenomenon, this sense of community — a key ingredient for resilience — seems to flourish more easily or more frequently in rural areas, so much so that community spirit is often said to be one of the features distinguishing rural from city living.

‘Community’ flourishes where human networks are small and open, making for rapid communications and visible personal circumstances. Local communications were perhaps always more efficient and comprehensive in rural areas due to partyline phone services and an effective bush telegraph, roles now largely adopted by social media.

The visibility of personal circumstances is not always a positive thing. It is a major contributor to stigma, which inhibits help-seeking in rural areas among some population groups in some circumstances.

The prosaic signs of community spirit and connectedness include a willingness by people to roll up their sleeves and get involved in work towards a shared local purpose; a can-do attitude witnessed in spades over recent months, with some local communities already rebuilding in earnest.

Occasionally, though, we should perhaps pause and consider the possibility that replication of patterns and structures that existed before the firestorms may not represent resilience. Such a return to the status quo may run counter to the adoption of new, more desirable, regulations relating to such things as where houses are built, how they are constructed, and what fire precautions are required. Not just building back, but Building Back Better, as framed by the government.

When the fires are out and the rebuilding is underway, it is to be hoped that the public and its governments maintain an appropriate focus on the communities of rural and remote Australia. It is vital that they do so because the conditions that exist — not just in times of crisis but in good times as well — are in some respects quite different from those in the major cities, requiring policies and programs that fit.

Resilience enhanced?

Rural communities do not need or want to always be seen through a deficit lens. Despite the real and ongoing challenges they face, people from rural and remote areas frequently score higher on self-perceived notions of ‘happiness’. It is not clear what the main reasons for this are, but they are likely to include the benefits of a stronger sense of community.

However there is a risk involved in this. Greater community connectedness must not be seen as an alternative to or replacement for services provided by governments and paid for from the public purse.

Resilience is not a reason to let governments off the hook as service providers whose challenge is providing equivalent access to such things as health, education, broadband or aged and disability services to people in all parts of the nation.

It’s not as if resilience and public services are a zero-sum game. And rural people want to be thought about and properly considered in good times as well as bad.

Given the local, spontaneous, community-driven nature of resilience, the active involvement of the government in enhancing it may be ambitious or even counter-intuitive. If it is to proceed as the Prime Minister has indicated, there needs to be an agreed definition of what it is, and agreed measures to quantify its existence. It should be possible to design research which will meet the need for both agreed definitions and empirical research on its existence and effectiveness in various locations.

When defining resilience some of the urban (and rural) myths must be exposed. Rural males have sometimes been thought of as ‘resilient’ because of their unwillingness to see a doctor or to care for their own health in other ways. This is to confuse resilience with pride, risk aversion and fear.

Health services in rural areas — although stretched by large distances, higher costs and workforce shortages — must be prepared to meet the challenges posed by environmental disasters such as floods and fires, animal-borne infections, and epidemics. The responses of health agencies during the bushfires will be a matter for consideration once the emergencies have passed. And, unfortunately, those same health services may soon be tested in relation to a new epidemic.

It may be short of resources, but in a cultural sense Australia’s rural health sector is well-equipped for disaster management. It has a strong values base, centering universality, equity and compassion.

Resilience is a second-best approach

The systematic review quoted earlier drew a very practical conclusion:

“In spite of the differences in conception and application, there are well understood elements that are widely proposed as important for a resilient community. A focus on these individual elements may be more productive than attempting to define and study community resilience as a distinct concept.”

And what of the choice between disaster prevention and enhanced resilience?

Of course it’s not either/or, but given a choice between disaster prevention and resilience, any rational being would choose the former. The best bet is to be without adversity and unhappiness in the first place.

Occasionally since the May 2019 election people have wondered, rhetorically, just how quiet the Prime Minister wants Australians to be.

It is to be hoped that the Quiet Australians — whoever and wherever they are — appreciate the basic after-the-event connotation of resilience, and do not allow it to displace or reduce Australia’s efforts to minimise carbon emissions.

It’s more important and more rational to prevent the need for a community to rebound than to enhance its ability to do so.

Climate change ‘resilience’ must not be allowed to morph into climate change ‘silence’.