Led by Barnaby Joyce the National Party is again missing the opportunity to invest in serious reform and improvement of rural health services. Instead it is pursuing a national resource agenda in just 9 of Australia’s 47 rural electorates. This provides manna for large multinationals but leaves people in the other 38 rural electorates with poor prospects for improved health and health services.

In the 2022 election campaign Barnaby Joyce has had his chequebook out to pay for some relatively small local gifts along The Wombat Trail. Recent mentions have included $25 million for an upgrade of the Shepparton Sports Stadium; $600,000 to improve amenities at the Armidale Rams Rugby League Club; and $3.3 million to the Burdekin Shire Council to expand the Ayr Industrial Estate.

One of the trickiest things about such proposals is whether, should the Coalition be returned, they will be supported by the Liberal Party and so become real commitments in the context of a Budget.

But we need to look elsewhere for the real news on what the National Party is doing. The serious money promised by the Nationals for ‘the regions’ is for major infrastructure work in a small number of mining areas, their railheads and associated infrastructure.

Despite its claims, the National Party has no appetite for direct investment in better rural health services across the whole of rural Australia. Instead, it is happy to rely on the trickle-down health benefits from resource industries, many of which are run by large multinational corporations. The exception is $146 million for the bottomless pit that is the program to try to improve the distribution of GPs.

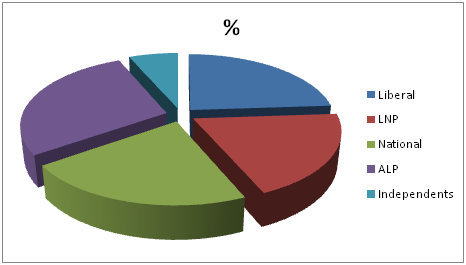

The narrow focus of the National Party becomes less of a concern when one identifies the proportion of truly rural electorates it holds. Right now it holds just 10 of 47 electorates that are properly ‘rural’. The Liberal Party holds 13 and the ALP 12. The Liberal National Party (LNP) has nine – all of them in Queensland – meaning that the Coalition as a whole (Liberal plus LNP pus Nationals) has 32 of 47, or 68 per cent. Three rural seats are held by Independents.

(Note: members of the LNP who are elected can choose to join the National Party’s caucus rather than the Liberals’. This adds further confusion to what is already a bizarre parliamentary arrangement.)

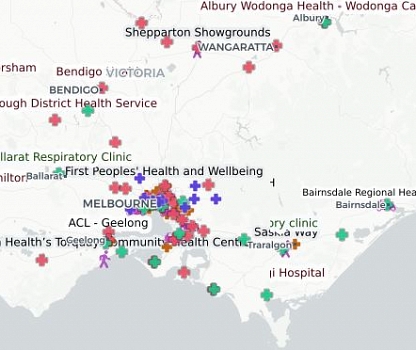

‘Rural Electorates’ 2019-2022: as defined by AEC classification plus area

| Party | AEC Provincial | AEC Rural | AEC Outer Metro. | Total ‘Rural electorates’ | % |

| Liberal | 2 | 10 | 1 | 13 | 28 |

| LNP | 3 | 6 | 9 | 19 | |

| Nationals | 1 | 9 | 10 | 21 | |

| ALP | 4 | 7 | 1 | 12 | 26 |

| Independents | 0 | 3 | 3 | 6 | |

| Adjusted total | 10 | 35 | 2 | 47 | 100 |

These numbers are based on two criteria. The first is the Australian Electoral Commission’s (AEC’s) categorisation of each of the 151 federal divisions (electorates) to one of four ‘demographic ratings’ on the basis of the location of enrolled voters. The third and fourth categories are Provincial and Rural. Those deemed Provincial are “outside capital cities, but with a majority of enrolment in major provincial cities”. The AEC’s Rural electorates are those “outside capital cities and without majority of their enrolment in major provincial cities”.

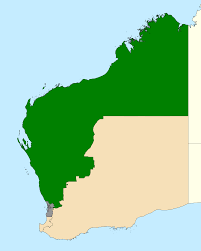

The second criterion for inclusion in the list is spatial size (area). Whatever their AEC classification, electorates of less than 1,913km² are excluded. (This is the size of the of the ACT electorate of Bean contested for the first time in 2019. Although it is part of the Bush Capital, no-one would dare suggest that it is ‘rural’! By way of comparison, Eden-Monaro has an area of 41,617 km² and Durack in WA 1,383,954km2.)

Of the 151 federal electorates, the AEC classifies 23 as Provincial and 38 as Rural. Thirteen AEC-Provincials and three AEC-Rurals are excluded on the basis of small size. They include Geelong, Gosford, three seats in Newcastle, Townsville, the Blue Mountains and the Gold Coast. Eight of the 16 excluded are held by the ALP.

The AEC’s 61 less 16, plus two AEC-Outer Metros (included on the basis of large area) makes 47. A list of the 47 rural electorates as defined by these criteria is at the foot of this article.

Rural electorates by Party, 2019-2022

Rural health v. regional infrastructure

The National Party refers to rural and remote areas as ‘the regions’. To the extent that they treat rural affairs as a priority at all, it is through a focus on mineral-rich regions that underpin Australia’s export income, GDP and affluence.

But the majority of Australia’s rural and remote people are not in such regions. They are in rural or regional centres or small country towns with mixed economies based on agriculture, service sectors (especially health and education), retail, tourism and transportation.

The most important thing about Barnaby Joyce’s return to leadership of the National Party was not the impact of renewed leadership but the opportunity to re-negotiate the secret deal with the Prime Minister. Joyce seems to have demanded a high price for Nationals’ support for – or at least acquiescence to – a policy of net zero emissions by 2050. It remains to be seen whether this was a core promise or whether it is “all over bar the shouting”.

Given its secrecy, the precise dollar figure extracted by Barnaby Joyce this time is unknown. The AFR has reported that, in addition to the one extra seat in Cabinet, the cost will be $17-34 billion over the coming decade. Budget documents show $17 billion in extra spending for road and rail projects, $6.9 billion for water infrastructure projects (dams) in regional communities, and $2 billion for a “regional accelerator program to drive transformative economic growth and productivity in regional areas”.

Armed with this treasure chest, since his return to leadership of the Party, Joyce has made massive budgetary promises to four regions: the Pilbara, the Northern Territory (including Darwin), the Hunter, and North and Central Queensland. These are critical for Australia’s economic wellbeing. And no-one should begrudge them the support they will need to maintain their enormous economic contributions while the economy as a whole is transitioning to lower dependence on carbon.

But these four regions are contained within just nine of the 47 rural electorates. The Pilbara and associated infrastructure are in Durack, and the Northern Territory comprises two electorates. The chief mineral resource operations of North and Central Queensland are in five electorates: Leichhardt, Kennedy, Dawson, Flynn and Capricornia. (Herbert is less than 100 km² in size and provincial.) Many of the mineral resources currently being exploited in New South Wales are in the seat of Hunter, with three seats in Newcastle also heavily engaged.

What about the people of the other 38 rural electorates?

It is not a matter of investment in mining infrastructure being a waste. The nation is very heavily dependent on mineral exports. But following his success in taking the Prime Minister to the cleaners in their secret agreement, Barnaby Joyce has so far failed to recognise the importance of reform of the rural health sector and the integration of improvements in the social determinants across all parts of the country.

Trickle-down or crumbs from the table is no way to treat the people of 38 rural electorates covering places like Uralla and Eucumbene, Kojonup and Kempsey, Port Augusta, Port Arthur and Port Fairy. It will do nothing in the short term for people in these areas who are unemployed, living with a disability, hoping to age in place, find it difficult to access education, or experience significant disease risk factors.

Australia’s 47 Rural Electorates

| AEC Rural | Held by | State | |

| Dawson | LNP | Queensland | |

| Flynn | LNP | Queensland | |

| Leichhardt | LNP | Queensland | |

| Maranoa | LNP | Queensland | |

| Wide Bay | LNP | Queensland | |

| Wright | LNP | Queensland | |

| Farrer | Liberal | New South Wales | |

| Barker | Liberal | South Australia | |

| Grey | Liberal | South Australia | |

| Braddon | Liberal | Tasmania | |

| Casey | Liberal | Victoria | |

| Monash | Liberal | Victoria | |

| Wannon | Liberal | Victoria | |

| Durack | Liberal | WA | |

| Forrest | Liberal | WA | |

| O’Connor | Liberal | WA | |

| Lyons | ALP | Tasmania | |

| McEwen | ALP | Victoria | |

| Eden-Monaro | ALP | New South Wales | |

| Gilmore | ALP | New South Wales | |

| Hunter | ALP | New South Wales | |

| Richmond | ALP | New South Wales | |

| Lingiari | ALP | Northern Territory | |

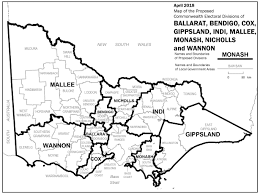

| Gippsland | Nationals | Victoria | |

| Mallee | Nationals | Victoria | |

| Nicholls | Nationals | Victoria | |

| Calare | Nationals | New South Wales | |

| Lyne | Nationals | New South Wales | |

| New England | Nationals | New South Wales | |

| Page | Nationals | New South Wales | |

| Parkes | Nationals | New South Wales | |

| Riverina | Nationals | New South Wales | |

| Indi | Independent | Victoria | |

| Kennedy | Independent | Queensland | |

| Mayo | Independent | South Australia | |

| AEC Provincials | Held by | State | |

| Bass | Liberal | Tasmania | |

| Capricornia | LNP | Queensland | |

| Groom | LNP | Queensland | |

| Hinkler | LNP | Queensland | |

| Cowper | Nationals | New South Wales | |

| Hume | Liberal | New South Wales | |

| Ballarat | ALP | Victoria | |

| Bendigo | ALP | Victoria | |

| Corangamite | ALP | Victoria | |

| Blair | ALP | Queensland | |

| AEC Outer Metro. | |||

| Canning | Liberal | WA | |

| Franklin | ALP | Tasmania | |