Important: the opinion Duncan Kerr wrote on dual citizenship in 1989 is reprinted here without alteration.

Duncan Kerr was the member for Denison in the House of Reps. from 1987 to 2010. In January 1989 he wrote a legal opinion for his Parliamentary colleagues about Section 44(i) of the Constitution, in which – inter alia – he discussed joint Australian-British citizenship and the fact that people may be citizens of other countries without their knowledge. Given the current situation affecting a number of Australian Parliamentarians, his discussion makes fascinating reading and, due no doubt to his target audience at the time, it is relatively accessible to those not expert in legal matters.

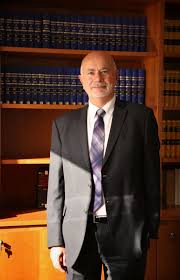

Duncan Kerr was Minister for Justice between 1993 and 1996 and for a period in 1993 was also Attorney-General. He is now a Judge of the Federal Court of Australia and recently completed a five-year term as President of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal.

photo credit: James Alcock

To help those of us who are not trained in the law to understand the current situation, the opinion Kerr wrote on dual citizenship in 1989 is reprinted here without alteration.

26 November 1992

Duncan Kerr MHR

Federal Member for Denison

Memorandum to ALP Members and Senators

Dual citizenship

In early 1989, at the request of several colleagues, I circulated a legal opinion to all ALP members and senators advising as to the interpretation of section 44 (i) of the Australian Constitution and associated issues.

The recent decision in Phil Cleary’s case has clarified a number of these issues but has left others unanswered – in particular whether the United Kingdom is now to be regarded as a ‘foreign power’.

This question is important because a number of members of the Australian Parliament still retain British citizenship in addition to their Australian citizenship. I also draw attention to the fact that people may even be citizens of other countries without their knowledge.

Because of the currency of these issues I am taking the liberty of recirculating my earlier opinion. The opinion is entirely consistent with the majority judgments in the Cleary case and requires no modification.

I would be happy to discuss the implications of the Cleary Decision with any colleague.

Duncan Kerr MHR

Federal member for Denison

photo credit: Dean Sewell

Opinion (January 1989)

I have been asked to advise as to the proper construction of section 44(i) of the Australian Constitution in the light of recent correspondence sent to a large number of members of the Parliament raising the issues of the eligibility to sit as a member of either the House of Representatives or the Senate.

Section 44(i) provides –

"Any person who - (i) is under any acknowledgement of allegiance, obedience, or adherence to a foreign power, or is a subject or a citizen or entitled to the rights or privileges of the subject or a citizen of a foreign power: shall be incapable of being chosen or sitting as a Senator or a member of the House of Representatives."

Section 44(i) can conveniently be broken into two constituent elements; the first applying to a person “who is under any acknowledgement of allegiance, obedience, or adherence to a foreign power”; the second to a person “who is a subject or a citizen or entitled to the rights or privileges of a subject or citizen of a foreign power”.

Common to each element, is some relationship with a ‘foreign power’ and before commencing any further analysis it is worth first settling what constitutes a ‘foreign power’.

Foreign power

The term ‘foreign power’, meaning in this context a country not one’s own, is generally non-problematic. The one contentious question is whether the United Kingdom is now to be regarded as a ‘foreign power’.

This question is important because a number of members of the Australian Parliament retain British citizenship in addition to their Australian citizenship.

Before the adoption of the Constitution the Australian colonies, later the states, were not independent nations. Nor did federation affect this position. The British Empire continued to consist of one sovereign State and its colonies and dependencies. In 1901 Australia was still perceived as a British colony.

Indeed the Constitution uses language in section 34(ii) which shows that the framers could not have regarded the United Kingdom as being a ‘foreign power’ within the meaning of Section 44(i). That Section adopted as an interim qualification (until the Parliament otherwise provided) for eligibility to become a member of the House of Representatives and the Senate, inter-alia, citizenship of the United Kingdom.

However, Australia has now emerged as an independent nation with its own distinctive citizenship. Recognising this, recent changes to the Commonwealth Electoral Act (adopted following the recommendations of the 1981 Report by the Senate Standing Committee on Constitutional and Legal Affairs (The Constitutional Qualifications of Members of Parliament) have substituted Australian citizenship for previous qualifications which had until then permitted a non Australian ‘British subject’ to stand for election to the House of Representatives (now see Commonwealth Electoral Act Section 163(i)(b)).

The question therefore to be resolved is whether the sum of these changes are such as to now compel the term ‘foreign power’ in section 44(i) to be read as including the United Kingdom. Whilst not decisive of the issue the recent High Court decision Nolan v Minister for Immigration 80 ALR 561 suggests that the High Court is unlikely to favour an interpretation of the word ‘foreign’ that does not fully reflect the altered relationship between Australia and the United Kingdom.

Conceding that good arguments can be made to the contrary, my opinion is that the High Court would now regard the United Kingdom as a foreign power within the meaning of section 44(i) of the constitution. Paraphrasing the joint judgement of the High Court in Nolan: “It is not that the meaning of the word [foreign] had altered. That word is and always has been appropriate to describe the status, vis a vis a former colony which has emerged as an independent nation [and the former imperial nation]”.

Acts of allegiance

The first limb of section 44(i) applies to a person who is under any acknowledgement of allegiance, obedience or adherence to a foreign power. What disqualifies is the positive act of acknowledgement of a foreign loyalty whether or not it affects [sic] a change in the person’s status, citizenship or employment. Often however, such acknowledgement of allegiance would be implied by some change in status – for example, serving in the armed forces or public service of a foreign power.

Citizenship or rights of citizenship

The second limb of section 44(i) applies to any person who is “a subject or a citizen or entitled to the rights or privileges of a subject or a citizen of a foreign power”.

Many Australian citizens hold dual nationality. Some do so knowingly and voluntarily, some knowingly but involuntarily, others unknowingly and involuntarily. The position is complex because there is [sic] no uniform international guidelines for citizenship.

Every sovereign nation claims the right to determine for itself who it will regard as its nationals. Such decisions may be made capriciously. For example some foreign nations do not permit renunciation of their citizenship even if the person seeking to renounce that citizenship has taken other citizenship.

In fact, people will often be citizens of other nations without their knowledge. The complexity is well illustrated by the report of the Joint Committee on Foreign Affairs and Defence (1976) Dual Nationality at p. 2.

"Rules governing nationality generally range from the automatic loss of a former nationality on acquisition of another, to making it impossible to surrender a former nationality. Some countries confer their citizenship on successive generations regardless of the country of birth. A consequence of this latter situation is that many Australians are unknowingly dual nationals and there is no way of determining with certainty who or how many are in this category."

Given the obvious potential for injustice were all Australians who either unknowingly or involuntarily possess dual citizenship to be incapable of serving in the Australian Parliament, such a construction would, doubtless, be avoided by the High Court unless that construction was compelling. In my opinion it is not.

The better view is, it is submitted, that the question of whether a person is a subject or citizen or entitled to the rights or privileges of a subject or citizen of a foreign power is one of fact to be ascertained by asking the question, does the person in question possess in fact any of the attributes which connote entitlement to foreign citizenship or the rights of such. This is a practical question, not one of foreign law to be ascertained by applying citizenship rules of one or another foreign nation to that person’s status.

An illustration of the application of this test can be given by the case of a person who unknowingly possesses dual citizenship. As an unknowing possessor, such a person would have no practical links with another nation and no question of loyalty to, or citizenship of, a ‘foreign power’ could arise. However such a person would come within section 44(i) if upon becoming aware of such a previously unknown right to citizenship, he or she acknowledges that status or takes advantage of it in any way – for example, travelling on that country’s passport.

A second illustration is that the proposed test would permit informal renunciation of unsought dual citizenship where formal legal renunciation is not possible.

This approach has the merit of providing a constitutionally autochthonous test and avoiding the absurd logic that would allow, for example, a decision of a mischievous foreign nation to wreck the functioning of the Parliament by extending that nation’s unsought and unrenounceable citizenship to all members of the Australian Senate and House of Representatives.

Whilst my view conflicts with the opinion of the 1981 Report of the Senate Standing Committee on Constitutional and Legal Affairs The Constitutional Qualifications of a Member of Parliament, it is broadly consistent with the conclusions expressed by Lumb and Ryan The Constitution of the Commonwealth Australia (3rd ed.) (at para. 167) who give as an example of the application of the second limb of Section 44(i), the case “where an Australian naturalized citizen voluntarily retains the privileges or rights attaching to his former citizenship”. [emphasis mine]

It is also is in conformity with the obiter remarks of the High Court (sitting as the Court of Disputed Returns) in Nile v Wood (1988) 76 ALR 91 at p. 96

"it would seem that section 44(i) relates only to a person who has formally or informally acknowledged allegiance, obedience or adherence to a foreign power and who has not withdrawn or revoked that acknowledgement".

Challenges to a member’s capacity to hold office

There are two methods an individual can use to challenge a member’s entitlement to hold office, either pursuant to the Commonwealth Electoral Act or pursuant to the Common Informers (Parliamentary Disqualifications) Act. In addition either house itself may exercise its inherent powers to decide any question as to its own membership Bradlaugh v Gossett (1884) 12 QBD 271. Given the background to this opinion I will confine my comments to those circumstances in which a concerned individual can challenge a member’s entitlement to sit.

The right of an individual to challenge under the Commonwealth Electoral Act is strictly limited: see sections 355, 356 and 358. For the purpose of this advice, the most relevant limitations are (1) that a petition challenging an election can only be initiated by another candidate or an elector qualified to vote in the election to be challenged and (2) that such a petition must be filed within 40 days of the return of the writ for the election. Because the 40 days referred to has now expired the provisions of this Act can no longer be availed of during the life of the present Parliament.

I turn now to the provisions of the Common Informers (Parliamentary Disqualifications) Act. Surprisingly, given the obvious intention to dispose promptly of potential challenges evidenced by the Commonwealth Electoral Act, there is no time limit prescribed for the bringing of a challenge under the Common Informers (Parliamentary Disqualifications) Act. That Act permits any person to sue (for monetary damages) any person who sits in either house “while he was a person declared by the Constitution to be incapable of so sitting”. Implicit in this jurisdiction must be the right of the High Court to determine questions of eligibility under, inter-alia, section 44(i). As a result is possible that an intermeddler can, at any time, commence proceedings in the High Court challenging the capacity of a member to sit. Given the sound policy reasons which apply to restrict the period for challenges to elections generally, it might be thought appropriate to amend the Act to also provide some appropriate limitation periods for actions under the Common Informers (Parliamentary Disqualifications) Act.

Renunciation of foreign citizenship

Assuming that some members may be at least arguably in jeopardy because of Section 44(i), those that are would be well advised, as a matter of caution, to take steps to renounce any foreign citizenship which they may have previously acknowledged before contesting any further election.

Whilst that will not remove the threat of an action being brought under the Common Informers provisions (discussed above) during the life of the present Parliament, it will remove the possibility of any subsequent challenge should the member concerned be later re-elected.

Most, but not all, nations permit renunciation. [See for example Section 19 of the British Nationality Act and Part III and Schedule 5 of the British Nationality (General) Regulations No. 86 of 1982 which permit a citizen of the United Kingdom to make a declaration renouncing that citizenship. A copy of the relevant provisions is annexed.]

One practical consideration however needs to be mentioned. There has been at least one recent incident of a breach of confidence by an embassy in similar circumstances. Given that the act of a member in renouncing a foreign citizenship, were it to become public knowledge, may itself trigger a suit under the common informers procedure, common sense would suggest leaving the matter of renunciation until some time closer to the end of the term of the present Parliament so as to minimise the likelihood of such litigation.

Finally, I should indicate my view that if a foreign nation does not permit renunciation of its citizenship, all that is required of a Member is that he or she clearly and unambiguously revoke any acknowledgement of that other citizenship and take care thereafter never to do anything that could be construed as acknowledging or taking advantage of that other citizenship.

Duncan Kerr

Chambers

January 23, 1989