On Friday 27 August National Cabinet discussed plans for the vaccination of 12-15 year olds and gave further consideration to the use of the Doherty Institute’s model of the dynamics of covid-19 infection and vaccination. The agendas for its future meetings should include the following five matters.

1 – The nation needs and deserves a detailed schedule of the numbers of various vaccines due to be delivered to Australia in the next 12 months. It is understood that there may be some unavoidable delays, even when contracts have been entered into. These could include the sort of batch quality issues currently being experienced in Japan with Moderna.

Everyone is now aware that the ‘dark matter’ that has hung over Australia’s vaccination program from the very beginning is insufficient supply. The public and those working on the pandemic need to know what the expected schedule is. Apart from anything else, such a schedule is required in order to agree to the second of these five agenda items: a new priority order for vaccination.

2 – A new priority order for vaccinations must be drawn up for all to see and discuss. It would be a tragedy if those groups which were in 1a all those months ago were to be pushed down the ranking before they have been accorded what they were originally promised: to have all of their group fully vaccinated.

However the overriding purpose of vaccination has shifted from the situation in which, with very little Covid in Australia, the most important criterion for ranking was vulnerability to serious illness and death. Vaccination is now a key asset in efforts to reduce the number of infections. And even though it would be a tragedy, it is now clear that some tragedies simply will not be avoided.

If year 12 students in the most affected LGAs in Sydney are to be a higher priority than people in aged care facilities, let’s have public discussion and understand the reasons why this is so.

If it is simply impossible to deliver to the Aboriginal Medical Service in Orange the 900 doses a fortnight it needs, let’s understand that now so that remedial action can be taken immediately. The alternative is to dissemble, to let the actual situation dribble out, delaying mitigating action and making the situation even worse.

To some extent the responsible agencies have hidden behind the phrase ‘The Most Vulnerable’. No-one could argue against vaccinating ‘the most vulnerable’ first. However someone has to convert the phrase into action.

From the beginning, to this vulnerability criterion were added practical, commonsense criteria about the potential seriousness of the impact on health and other essential services of staff having to isolate and be away from work. That remains a critical criterion.

The new criteria for allocation include geographical and demographic characteristics. Where you live and what contribution you are likely to make to spread of the disease have become as important as the extent to which you are likely to be severely affected by the condition.

If vaccine is still in short supply in September and October, very difficult decisions will have to be taken. Teenagers or the 20-39 year olds? Home aged care workers or teachers? People living with disability or those in remote areas with little access to health services?

3 – The Commonwealth must take the lead in developing protocols and systems for determining which employees in which sectors will have a mandated requirement for vaccination.

Notwithstanding the legal complexities that apply, this is too important an issue to leave to individual companies or workplaces. If it is agreed, for instance, that all hospital staff, teachers, childcare workers or food distributors should have mandated vaccination, then the implications for distribution of available vaccine (2 above) can be factored in.

Individual entities such as District Health Boards for hospitals and Departments of Education for schools can be expected to deal with specific matters such as how to manage people on their staffs who have sound reasons for avoiding vaccination.

This issue will have to be considered in conjunction with plans for a ‘vaccine passport’ (by whatever name).

4 – if he hasn’t already got one, Lieutenant-General Frewen needs to appoint a supremo to ensure that resources and other encouragement are provided to the wide range of community groups that, between them, are having success in helping to ensure that particular groups who are marginalised are getting vaccinated. There are also many valuable local initiatives providing care for communities affected by the pandemic in other ways.

Absolutely no ‘centralisation’ is required but support, information, data and publicity will all help such effort. The circulation of case studies can contribute to these practical remedies and to the morale of communities everywhere. Support should be provided by both state and federal governments to ensure that the efforts of such groups are optimised.

The new emergency brought about by Delta is what has seen such community groups mobilised. Perhaps even community spirit needed a jolt to overcome complacency. Also, at last, the various jurisdictions have injected urgency into their management of covid, including through adopting practices that have been applied in other countries months ago. This includes flying squad type programs to target particular areas or groups of people, mobile clinics, and a range of incentives for getting vaccinated.

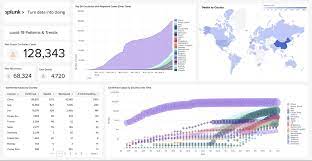

5 – Some appropriate, energised and capable agency needs to be commissioned to produce (for the public) data on all aspects of the pandemic and its management. One of the gravest and most surprising aspects of the pandemic to date has been the lack of good data at national, state, regional and demographic group levels. This needs to be rectified as a matter of urgency.

There is still much to be done in relation to the pandemic and the vaccination program in particular. With action on these five matters Australia can put the muddle behind it and move on to better ways and better days. Public discussion of the priorities for vaccinations (which priorities may or may not be new), informed by plentiful data, can help make sure that confidence replaces hesitancy.

It needs to be accepted that if supply remains inadequate some very challenging choices will have to be made about which people are the top priority and which will just have to be delayed.